-by

Varsha Singh

A nation’s literature is traditionally seen as a reflection of the values, tensions, myths and psychology that identify a national character. Countries resemble many things to many people. They are places, nations and communities. They are also ideas that change constantly in the minds of their people and in debates about the past and the future. Bendict Anderson defines nation as ‘an imagined community’. He maintains that the members of a nation never know each other, meet or hear each other, yet they still hold in common an image of who they are as a community of individuals.

How is a ‘common image’ passed on to children (and to people in general) in India? One of the ways in which an image is transmitted to a nation is through literature. Sarah Lorse (1997) writes that national literature are ‘consciously constructed pieces of the national culture’ and that literature is ‘an integral part of the process by which nation-states create themselves and distinguish themselves from other nations’. For young readers, national literatures play a crucial role in developing a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, of knowing who they are. In 1950, Australian author Miles Franklin argued that ‘without an indegenious literature people can remain alien in their own soil’.

Identity is not just a positive self concept. It is learning your place in the world with both humility and strength. It is, in the words of Vine Deloria, “accepting the responsibility to be a contributing member of a society”. Children also need to develop a strong identity to withstand the onslaughts of a negative hedonistic and materialistic world, fears engendered by terrorism, gender discrimination, and the pervasive culture of poverty that envelops many reservation and inner cities.

“ But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!”

The above mentioned quote from William Wordsworth’s “Ode, Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood”, perhaps: excellently illustrates what many of the current adult Indian population might just feel about the world of childhood and being a child. The contemporary approach towards Children’s literature in India has forever clung to this romantic image of childhood.

Children’s literature in India is meant for readers and listeners up to approximately twelve years of age and is often exemplified with detailed illustrations. The term is utilised in senses which at times can also exclude young-adult fiction, comic books, or other genres. It is also a known fact that books specifically written for children did begin to exist by the 17th century.

Children’s Literature during Ancient India

Like all primeval cultures, India too possesses its wonderful storytelling traditions since time immemorial, thus rendering Indian children’s literature as a distinctive oral as well as written genre. In most Indian families, stories were in fact, ‘just a grandmother away’. The Panchatantra, were stories told by Vishnu Sharma to three young princes as part of their education and teaching upon ‘intellligent living’. The structure of that very children’s literature from India, as the first instance of the original, as ‘frame story’, were in fact, several stories set within. Stories within stories were indeed a fascinating way of telling them to children, as they themselves made good use of this format most naturally in their own aptness of story-telling.

The other very enthralling aspect that comes up while tracing the history of the Panchatantra in Children’s literature in India are the umpteen styles of illustration, that accompanied the text – from cave paintings to rock-cut panels, from classical miniatures to Nepali folks. The classical and immortal series of Amar Chitra Katha have been adapted over and over again, each writer and illustrator harnessing inspiration from the original and ameliorating it further with their own style and imagination. Panchatantra under the genre of Children’s literature in India, have wondrously served as platform for inspiring regional as well as English story-tellers.

Children’s Literature in Medieval and Modern India

The medieval period for Children’s literature in India was also one of experimentation and symbolic representation, with Urdu stalwarts like Amir Khusro or Mirza Ghalib setting the balls rolling for an age of transformation or metamorphosis in illustrative or pictorial literature for children in India, which could varily be senses in the poetic pieces of Islam dominated India. However, all this is a part of a glorious past, remaining there exactly where it had remained, with the current scenario being vastly different. The rich metaphor and imagery, the original approach and sophisticated structure of the oral and written tradition of the yesteryears. Children’s literature in India is verily reflected in retellings and adaptations in a rather convoluted and refined mannner; many have been competently written, some well-written. But none have indeed ‘dared’ to capture the spirit of these stories. This is solely because if these stories are rewritten utilising the techniques, forms and structures of the oral or primeval telling, they would upset many of the pre-conceived notions about children’s stories. Whatever the factor is presented in the contemporary scenario, ancient Indian Children’s literature is perhaps the most heart-warming and enjoyable of the lot, differing vastly from any modern-day format; those stories were much closer to nature, with unshackled and unchained experiences, much like a child’s conversations and play.

There exists a special category for children’s literature in India, pertaining to books written not specifically for children, but which would be relished by them. Here one can find the Panchatantra, The Jataka Tales and many of the popular folk stories and nursery rhymes of the world being grossly incorporated. In fact, the arrival of the Europeans on Indian soil, particularly with the British Empire ruling, literature in India never did abide the same, with English as well as regional children’s literature in any given Indian language was being issued with full vigour and mass reception. The works of writers such as Sukumar Ray, Satyajit Ray, Rabindranath Tagore, R.K. Narayan, Ashokamitran, Basheer (in regional languages), Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, Ruskin Bond have swayed the much young reading section, young and old at different levels, in different voices.

Children’s Literature in Contemporary India

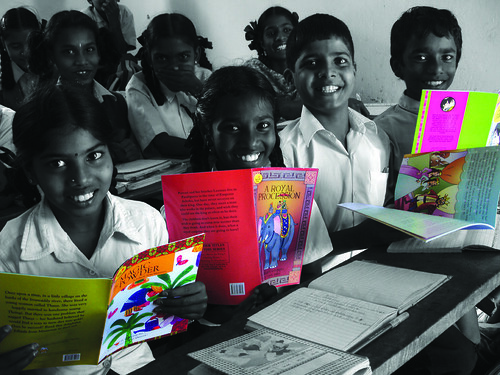

The printed Children’s literature in India bears a history of barely 150 years. But post Independence, ‘juvenile literature’ has witnessed a steep growth and development, despite several hurdles. Children’s literature in India is slowly, but securely struggling over the high walls of taboo, shaking off the ‘dry dust of didacticism’.

The existing literature on children and childhood in India has focused either on issues of child labour and state policies, or has left detailed psychoanalytic study of the history of growing up as a child. Of late literary critics and historians have produced important works on children’s literature and colonialism, on rearing of sons and the discourse of the “new” family, as well as on socialization and bringing up of the girl child. But unlike the Western historical literature, South Asia still does not have a social or cultural history of national life and identity of self with children as its primary focus. Recent scholars on other parts of Asia, however, have begun to address the issues of childhood from different aspects, starting from “domestic subversions” in colonial east Indies to “passages to modernity” through the day-care movement in Japan.

By following upon the existing literature on the periphery of children’s literature, now is the need to draw the Children’s Literature of India towards representing the nation and children’s indigence of developing a strong identity, in order to stagnate the assault of a hostile connoisseur and fiscal world, apprehensions invoked by rebellion, gender discrimination and the blatant dogma of subsistence.

By- Varsha Singh